IF you’re feeling down, you can always rely on a French philosopher to cheer you up.

Take, for example, André Comte-Sponville, who this week advised his public not to worry too much about catching Covid-19 because eventually they’ll all be dead anyway.

For a French penseur, he was actually pretty upbeat, saying he’s decided to stay happy because it’s good for his health.

That reminds me of the great English philosopher Monty Python who counselled: “Always look on the bright side of life,” a dictum which, set to music, is apparently top of the pops as the sign-off at British funerals.

Comte-Sponville is certainly more upbeat than some of his philosophical predecessors, such as Jean-Paul Sartre with his wrist-slashingly gloomy “Nausea”, or the great Albert Camus, who suggested the only thing a sane man could do in the face of the absurdity of existence was to top himself.

Neither of the latter were particularly anglophile. They may even have been slightly irritated by the mundane practicality of their English counterparts and their more workaday vision of la condition humaine.

Some French thinkers, however, were among their countrymen who developed an affinity for England, and for London in particular.

There has always been a two-way traffic between the great cities of Paris and London. While English escaping their country’s stifling moral strictures headed for Gay Paree, French radicals were fleeing to London. It was the safest European haven in the 19th century as no foreigner was expelled from Britain between 1823 and 1905.

There were so many of them, the French police ran an undercover operation to keep an eye on the exiled agitators in London.

Voltaire lived in Maiden Lane, off the Strand, in the 1720s when he came to London to promote his epic poem “La Henriade”, censored in France, and to have the local French Huguenot community print it for him.

He used to go to Drury Lane Theatre and met Pope and Swift and took Isaac Newton’s theories back home to France.

In his “Letters on the English,” Voltaire expresses admiration for the Anglican religion but finds hard-line protestants overly strict. “No operas, plays, or concerts are allowed in London on Sundays, and even cards are so expressly forbidden that none but persons of quality, and those we call the genteel, play on that day.” Sounds like the average English Sunday in the 1950s or a day in lockdown.

“The rest of the nation,” wrote Voltaire, “go either to church, to the tavern, or to see their mistresses.”

Madame d’Avot, who wrote her “Letters on England” after spending 1817-1818 in London, wasn’t a total convert. “The English show greater fairness to other peoples than they do to us,” she wrote, “because those others are behind in the march of civilisation and excite less understandable jealousy than between two rival nations.”

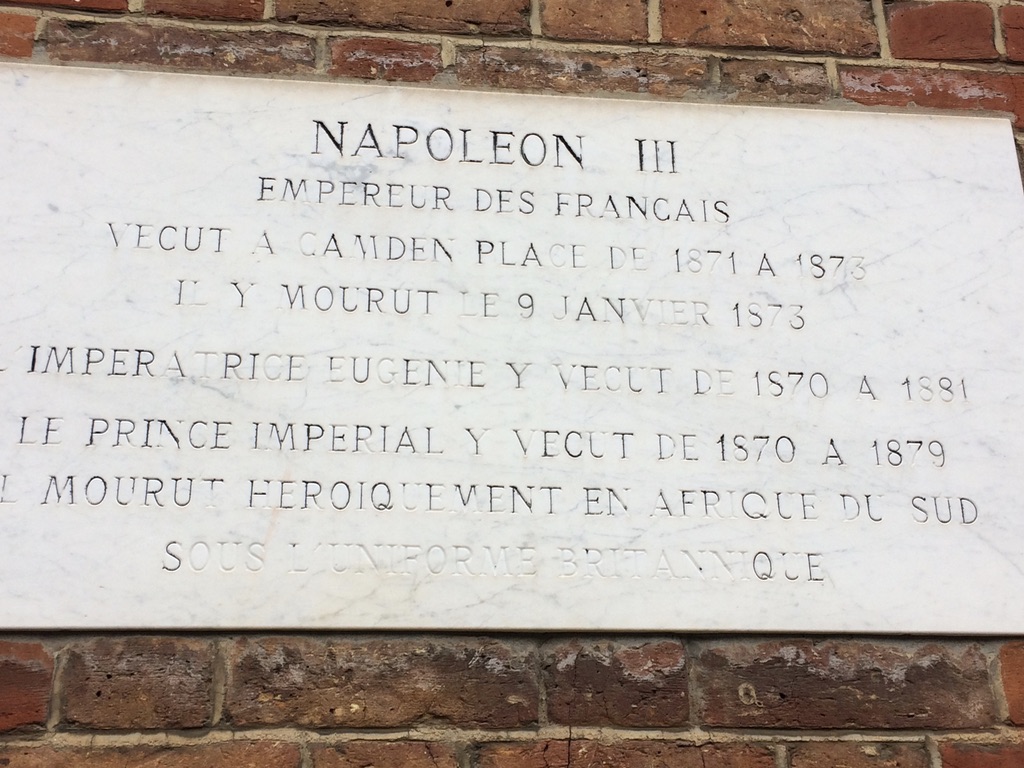

Napoleon III lived just outside London at Chislehurst after the French kicked him out (see today’s picture).

Later, the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline worked in London in the early part of the First World War. He even wrote a novel called “London Bridge”, set among the city’s underworld during the conflict.

Céline rather lost it in later years, churning out virulent anti-Semitic tracts before signing up as an active collaborator of the Nazis. So he wouldn’t really have fitted in with the Free French who were based in London in World War II.

Anyway, enough of that. Let’s leave the last uplifting word to André Comte-Sponville. “Today, on our TV screens, we see about 20 doctors for every economist,” he says. “It’s a health crisis, not the end of the world.”