LEADENHALL Market is a bit subdued these days, barely kept afloat by the reporters and occasional camera team who head there to update us on the pandemic-driven decline of the City of London.

Covid-weary hacks seeking insights from lippy millennials about the government’s latest indeciferable directive will naturally gravitate to Soho’s Old Compton Street around closing time.

To gauge the response of equally lippy retailers, however, they’ve taken to heading for Leadenhall, the grumbling ground zero of the Square Mile.

Sky, the BBC and the Standard have all visited and the Daily Mail has been round at least twice, latterly to chronicle the backlash over the government’s “chaotic new rules”.

It’s an appropriate place to sound out the vox populi since the market and its surroundings were at the dead centre of Roman London. If there had been a Radio Londinium around during the 2nd century Antonine Plague, no doubt its hacks would have headed to the neighbourhood.

Now, THAT was a pandemic! It swept across the empire from the Middle East and killed up to a third of the population in areas hardest hit. Londinium, a port and an important garrison, was particularly vulnerable.

The population declined as many fled. But for some it was a plus. Wealth became concentrated in fewer hands and the rich built ever larger and flashier town houses. The locals took to worshipping Apollo, the god of medicine and healing.

It was bad timing for a pandemic. The Romans had only a few decades earlier put the finishing touches to a new Forum, the second largest north of the Alps, with a basilica taller than Wren’s St Paul’s.

And, of course, it had a market, although it wasn’t yet called Leadenhall. If Roman remains elsewhere are anything to go by, it would have been heavy on fast food and takeaway.

You can almost imagine the intern from the Daily Londinium being sent down there to hear the lentil stew and spiced wine seller griping about the impact of the latest imperial anti-plague measures on walk-in trade.

There are remnants of the Roman age all over modern London, including bits of wall in the cellars of Leadenhall, most of it buried under centuries of subsequent development.

I’m just about old enough to remember the excitement when builders dug up the remains of a Temple of Mithras. Mind you, there wasn’t much else to get excited about in 1954 London.

The temple remains are now displayed in the bowels of the new Bloomberg building in Cannon Street. Worth a visit, although maybe a bit too son et lumière.

Underneath the Guildhall are the remains of an amphitheatre where up to 6,000 people could go to watch animal fights, gladiators and public executions.

Given the extent of this cultural treasure house, it’s amazing how little the Romans intrude into the London psyche. Maybe it’s because, unlike in Rome itself, or Nime or Trier, most of it is underground.

London goes weak at the knees when it recalls the city of Chaucer, Pepys or Dickens. But when it comes to the Romans, the attitude is very much: “What did the Romans ever do for us?”

It’s as if the poor old Romans were not so much forebears as interlopers, even though they founded the city and named it long before England was invented.

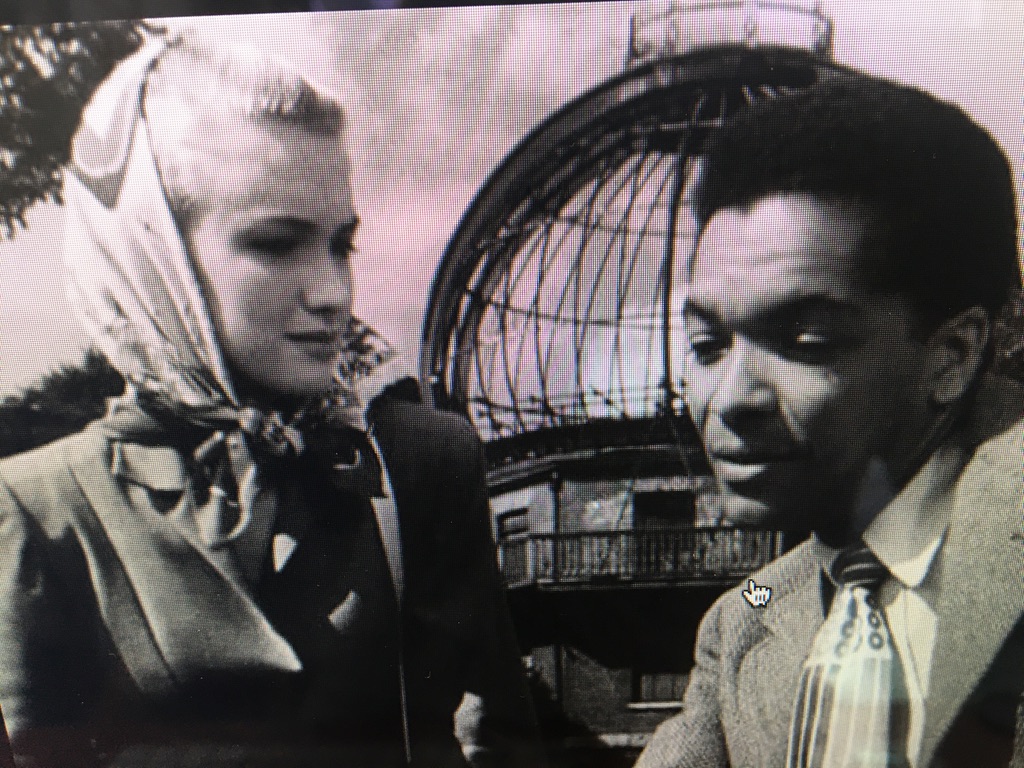

Then, as now, a lot of the inhabitants came from somewhere else. There were native Celts and Africans, Germanic mercenaries and slaves, Syrian merchants, Jews and early Christians (the latter tended to get lumped together), maybe even a few Italians.

Multicultural London, demonised by the self-imagined descendants of those Johnny-come-lately Anglo-Saxons, is definitely not a new phenomenon.

The Empire declined, the legions left, and London was abandoned. But, centuries later, once the continental newcomers had settled in and overcome their early obsession with Chelsea, they repopulated the Forum.

Leadenhall resumed its role as a central market. The poulterers and cheesemongers moved in. In the 15th century London Mayor Dick Whittington (yet another incomer) took a lease out on the place.

Its present incarnation is the handiwork of Horace Jones, the 19th century architect who also gave us Tower Bridge, a pastiche of a Scottish baronial castle that is London’s current identifying icon.

In normal times, Leadenhall is a hangout for Lloyd’s insurance brokers who work just around the corner. I confess it’s not my favourite market. There are a couple of decent pubs but there are too many chintzy shops and not enough poultry and cheese.

Anyway, it’s likely to overcome our present travails. There was an extended shutdown after about 400 AD but Leadenhall is still with us despite the grumbles.

Stop press: I’m Covid-negative. No, I didn’t ask for a test. No, I didn’t need it. At a time when families are being sent on 500-mile round trips to get a swab, I got mine unsolicited through the post.

It’s for some government-backed trial or other. I’m happy to help out, but a mate who did a rival trial got a 50 quid voucher. What did I get? Zilch!