KING’S Cross. For some people it’s been the stepping stone to a new adventure, for others it’s been the end of the line.

With varying degrees of aspiration, desperation and trepidation, generations of Scots and northerners took the night train south to the once grimy terminus to chance their arm in London, or as they used to call it, The Smoke.

Some of them, like Tom Courtenay’s fictional anti-hero in the 1963 film Billy Liar, bottled it at the last minute, leaving the glamourous Liz – Julie Christie – to set off alone on her London adventure.

The area around the former Great Northern Railway terminus and the Gothic folly of St Pancras next door has maintained its air of transitoriness despite a major clean-up in the 1990s intended to eclipse its reputation for prostitution and drugs.

Before that, predators lurked in the gloom of the old station entrance to lure northern teenage runaways straight off the platform and into their nefarious enterprises.

Those were the days when no self-respecting London TV noir would fail to include at least one scene of a traditional King’s Cross kerb-crawler eyeing the pavements for talent along the dark walls that hid the railway tracks.

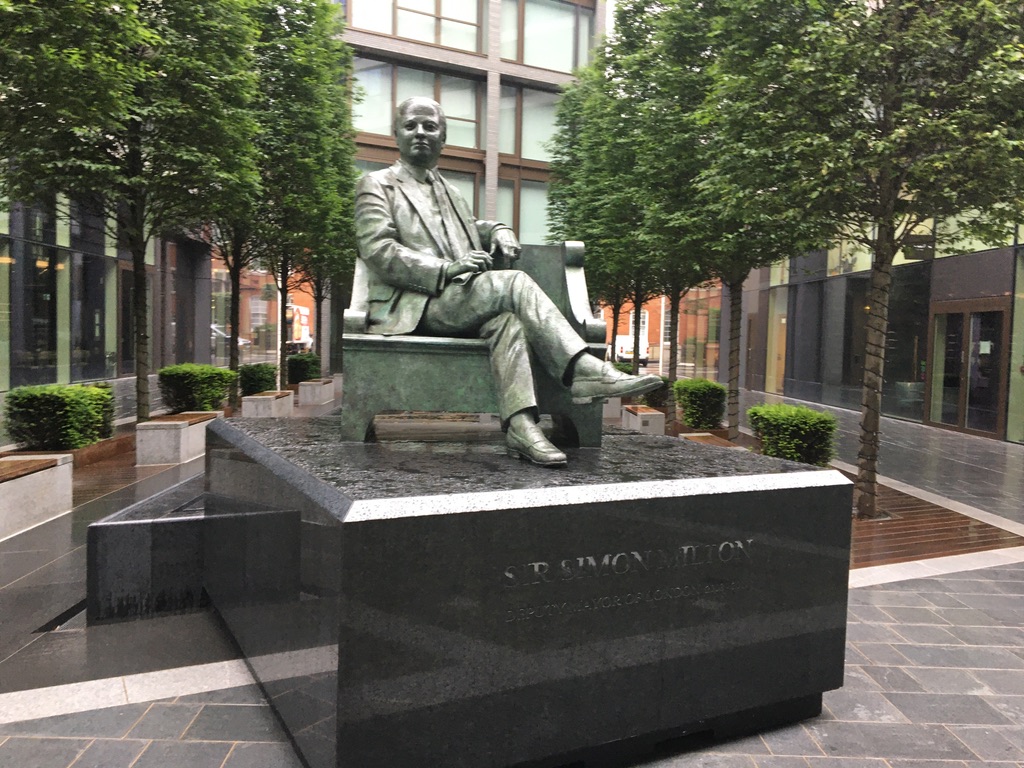

The old coal yards, gasholders and canalside warehouses to the north of the platforms are now the site of one of the largest 21st century regeneration projects in post-industrial, “world-beating” Britain.

The old pay-by-the-hour B&Bs and gloomy wino hangouts have been replaced by bijou artesan eateries. Incidentally, these have responded nobly to the lockdown by offering brown bag vegan takeaways and chilled Sauvignon at barely a score a head in order to keep the wolf from the door.

Over a couple of decades the British Library and the Guardian newspaper moved into the area and latterly the Francis Crick Institute life sciences hub, Europe’s biggest biomedical research centre, along with new museums and art galleries.

Google is in the process of building a £1 billion, 11-storey London HQ, its first such wholly-owned project outside the US, and one that was temporarily halted when one of its contractors went down with the coronavirus.

Arrivals these days seen hurrying out dragging their cabin bags are more likely to be weekend warriors commuting from Paris or Brussels as workseekers from Newcastle or adventure-seeking shopgirls from Stoke-on-Trent.

But, after dark, none of them linger long in the square. Despite the changes, King’s Cross has yet to quite shed its predatory feel.

Daytime is okay. Parents even bring their kids to see King Cross Station’s latest attraction, the Harry Potter Merchandise, Souvenirs and Collectables shop next to a sign for Platform 9 3/4 from which J.K. Rowling’s fictional child heroes headed off to school.

I used to pass for a while through just such a secret door at King’s Cross. I coudn’t find it this week so maybe, like the fictional platform entrance, it’s been bricked up.

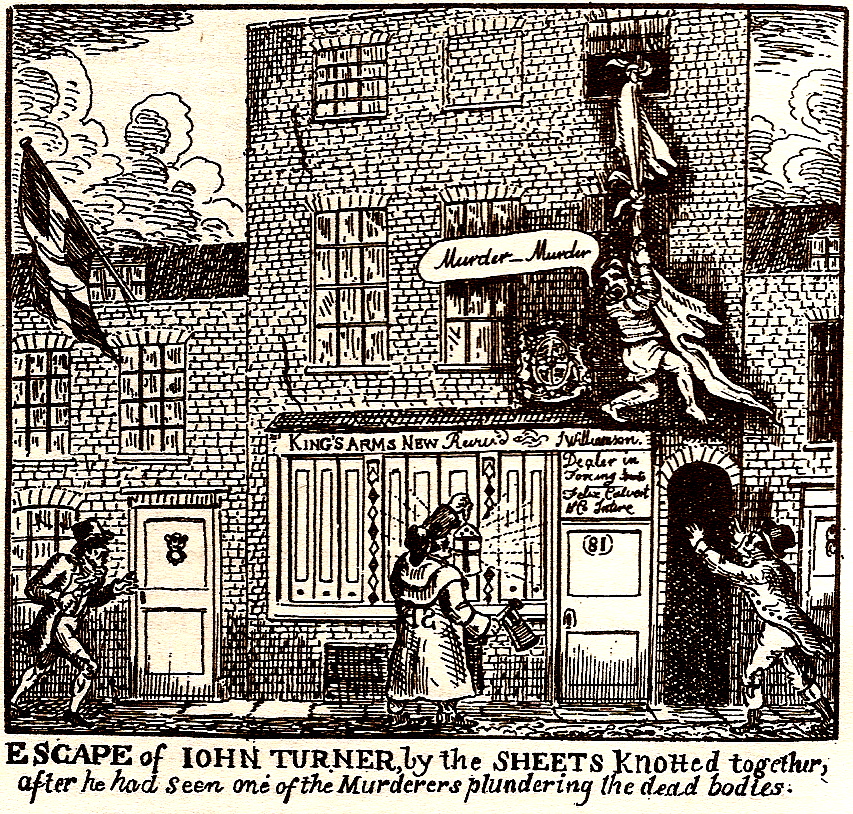

It was the gateway to a subterranean world as weird in its way as Hogwarts. Like the Phantom in the Paris Opera, you descended in the gloom to a vast labyrinth of workshops and storerooms that never saw the light of day.

Like him, you almost expected to reach an underground river, which in the case of King’s Cross would surely be the long ago boxed-in River Fleet.

One vast area was run by a Czech emigré who bought cheap sports gear from the eastern bloc and sold it at such a hefty mark-up that half was allowed to rot in the network of vaulted tunnels and dead ends.

The permanent crew were a bunch of cricket-mad lads from St Lucia who liked to haughtily stress their superior status by refusing to speak anything but creole French, except to shout orders at the native temps.

They were the only ones who got to drive the second-hand electric milk floats needed to ferry supplies around their underground domain.

Their foreman was an older, book-loving man, also from the Caribbean, who was transitioning from Jesus to socialism.

Where are they now? Where are the storerooms for that matter? It’s all trendy shops now where the descent to the underworld began. Maybe there’s still a secret entrance for the initiated just like at Platform 9 3/4.

Perhaps that parallel, subterranean King’s Cross still exists, beyond the ken of the new inhabitants at Google or the Crick. So, should you find yourself in the area one dark night, don’t go wandering through any unmarked doors.