THE graveyard at Hawksmoor’s St George-in-the-East is a dark place even in the spring sunshine.

Does the darkness come from the shade of the trees obscuring the faded headstones and concealing the presence of its solitary denizens? Or is it the shadow cast by the Radcliffe Highway Murders?

It was more solitary than usual this week. None of the usual winos, unless you count an old colleague and I sharing a spot of white to celebrate the easing of the lockdown.

There was a young woman incongruously sunbathing in a bikini and an older, larger one yelling “Come ‘ere, Porky” at her arthritic Staffordshire cross. Or was it Pikey? Certainly not Perky by the look of him.

The architectural critic Ian Nairn came here some years after the war to see the blitz-damaged 18th century church at a time when Wapping to the south was still dominated by the London docks and Whitechapel to the north by the gangster Kray twins.

“This is probably the hardest building to describe in London,” wrote Nairn. “This is a stage somewhere beyond fantasy…it is the more-than-real world of the drug addict’s dream.”

The church and its expansive grounds occupy part of what is still a faded boundary corridor barely touched by the East End gentrifiers.

At the time of the notorious murders in December 1811, the area was a squalid mix of overcrowded tenements, workshops and seamen’s lodging houses with a violent reputation even by the standards of early-19th century London.

The brutal slaughter of two families, 12 days apart and both within sight of the church, nevertheless sparked a moral panic, not only in the capital but across the country, spurred by the ghoulish reports in the emerging penny press.

The furore reached the highest in the land, from the newly-installed Prince Regent to the Tory government of the day. It was one factor in the eventual establishment of a professional police force to replace the elderly and often drunken watchmen who were supposed to keep the peace in areas such as the Highway.

The victims of the first attack on December 7 were Timothy Marr, a prosperous linen draper, his wife, their baby boy and the shop apprentice. Their bloody corpses were discovered by a maidservant, who had been sent out for oysters. Their skulls had been caved in with a chisel and hammer abandoned at the scene.

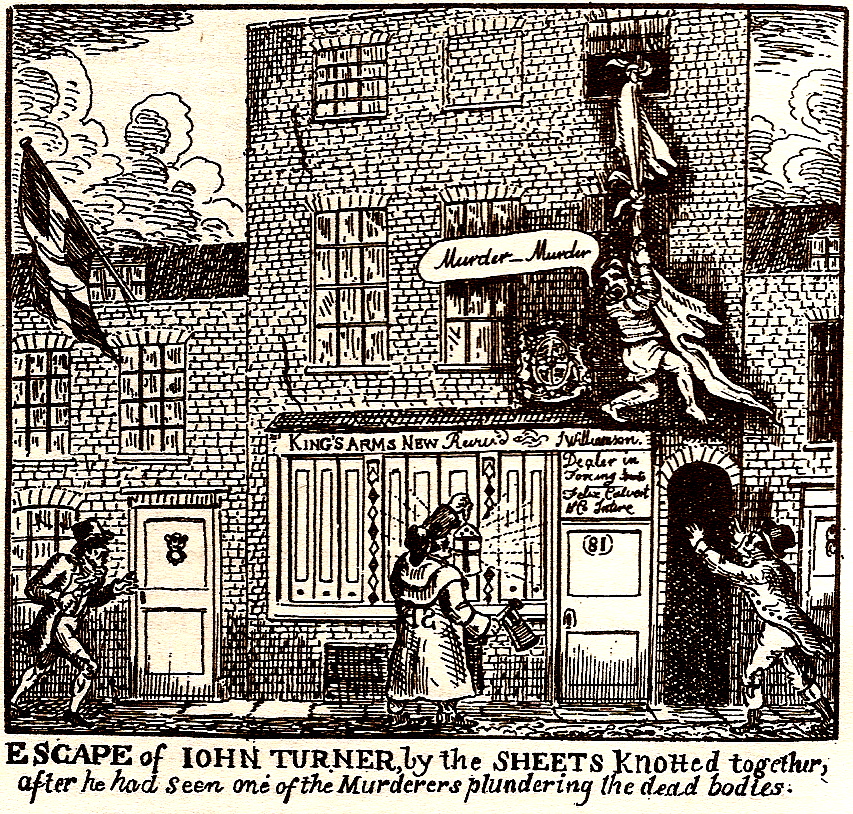

Then on December 19, a man was seen lowering himself by a sheet from the upper floor of the King’s Arms tavern, crying: “They are murdering people in the house.”

A constable and neighbours broke in to find the bodies of the 72-year-old landlord and his wife, both with their throats cut, and the mutilated corpse of a servant girl. A crowbar was found at the dead man’s side.

A hue and cry soon went up that a gang of foreign seamen must be responsible, specifically the Portuguese. The government was urged to post a proclamation from the Regent to be published locally in Portuguese and “oriental languages”. Three Portuguese were arrested but subsequently released after the intervention of their London consul.

Next, it was the turn of the Irish, widely suspected in the neighbourhood of having carried out the killings as part of a papist plot.

After a series of arrests, and following a tip-off from a Dane, suspicion fell on John Williams, a Scot. But, on December 27, before he could be committed for trial, he cheated the hangman by doing the job himself in his jail cell.

Although Williams’ guilt was never proven, the case was closed. In a judicial first for England, the authorities pandered to the outrage of the locals by having Williams’ corpse paraded past the scenes of his alleged crimes on the back of a cart. Some 180,000 people turned out to see him.

His body was dumped in an unmarked grave at the corner of St George’s graveyard.

Half a century later, workmen accidentally dug up his skelton along with the stake that had been posthumously thrust through his heart to prevent his spirit wandering.

Reflecting on his fate, Thomas de Quincy, of Confessions of an English Opium-eater fame, noted ironically that the murders were “the sublimest and most entire in their excellence”.

The killings were “amongst the few domestic events which, by the depth and expansion of horror attending them, had risen to the dignity of a national interest.”

Happy walking!

I quite like the idea of wheeling perpetrators past the site of their crimes. Perhaps the present government could be wheeled past care homes.

LikeLike

The way they’re going, that could well catch on.

LikeLike

Reading this the day after posting I wondered if at first it was a reference to Dominic Cummins, but being the musing post a pleasant afternoon with a friend and a glass of wine it seems an apt reflection on the times.

LikeLike

A day later, Rex, and I would somehow have managed to squeeze Cummings in!

LikeLike