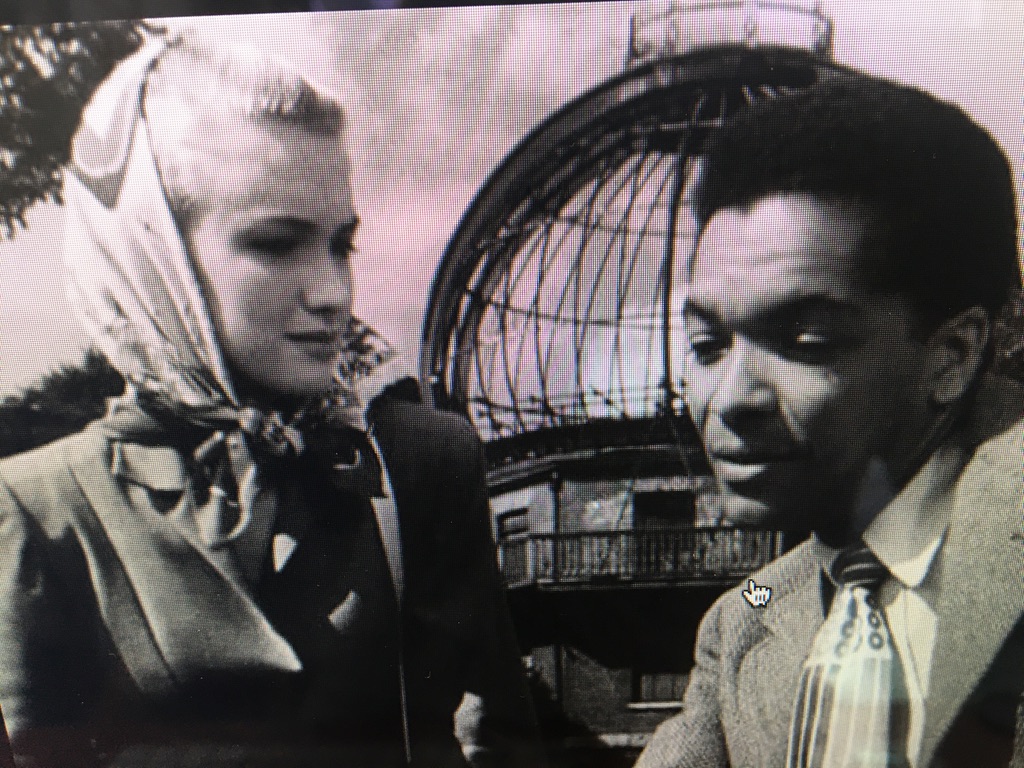

EARL Cameron, the Bermudan-born actor who starred in the 1951 film The Pool of London, died peacefully at home this week at the impressive age of 102.

His leading role as a Jamaican merchant sailor on a weekend of shore leave was a first for a black actor in British cinema. So too was his tentative screen romance with a white woman, played by Susan Shaw.

You could say, however, that his real co-star was south east London, which provides the backdrop to what is essentially a routine London noir about a jewel heist gone wrong.

Filmgoers used to having their weekly diet of romance or drama set in a Mayfair drawing room or an English country house were instead treated to a crime story made largely on location at the wharves in Bermondsey and at the Borough, Camberwell and Greenwich.

There are scenes set in Borough Market and Southwark Cathedral.

One of Cameron’s shipmates even jumps on a tram that will take him to New Cross, although either the budget or the plot precluded filming that far into the south east hinterland.

The Pool is still worth watching for its its critique of contemporary racial attitudes but also for its snapshot of a changing London emerging from the post-war grime with many of its habits and social mores still intact.

Some scenes are set at the Camberwell Palace of Varieties, an old fashioned music hall where in those days boys were still employed to set out the limelight lamps ahead of an evening of songs, jokes and acrobatics.

Within five years, the Palace had shut down and soon afterwards its ornate interior was demolished.

As for the trams, one character remarks that they too will soon be scrapped.

Much of the action takes place around the south bank of the pool of London where The Dunbar has moored after its voyage from Rotterdam. The crew prepares for a night ashore by stuffing their pockets with innocent bits of contraband, pocket watches and nylon stockings, to sneak past the customs men.

The Scottish chief engineer, played by the sonorous James Robertson Justice, opts to stay on board with a couple of bottles of brandy for company. Of London, he says: “Walk within the shadow of its walls and what do you find, filth and misery.”

On a boat trip to Greenwich, Cameron’s character, Johnny, explains the significance of longditude to his wide-eyed new girlfriend and reflects on the problems of race. “You wonder why one man’s born white and another not,” he muses. “It matters. Maybe one day it won’t.”

Perhaps we haven’t got there yet, as Cameron himself reflected in old age.

Having acted on the stage after arriving in Britain in 1939, The Pool of London was his screen breakthrough. He went on to win prominent parts in cinema and television for the rest of his career, including a supporting role in the Bond film Thunderball.

“Unless it was specified that this was a part for a black actor, they would never consider a black actor for the part,” he recalled in a 100th birthday interview. “And they would never consider changing a white part to a black part. I got mostly small parts, and that was extremely frustrating – not just for me but for other black actors.”

His breakthrough 1951 film highlights the prevailing prejudices, just a couple of years after the arrival of the Empire Windrush marked the start of large-scale immigration from the Caribbean. (Sadly, some members of that generation are still struggling for compensation from a government that illegally kicked them out).

“They’re all the same,” says one character as Johnny is ejected from a pub. “You must be hard up to go with him,” a unsympathetic white woman sneers at his girlfriend.

There are some jarring notes. The “nice” girls all speak with cut-glass, middle class accents while only the gangsters’ molls speak Sarf London.

Much has changed in the area in the decades since the film was made – although many would say not enough.

When Johnny asks for directions to Camberwell Green, he’s told to get the 42 bus on Tower Bridge. That’s a route that opened in 1912 and is still running to this day. At least some things in south east London never change.

Another enjoyable trip down memory lane. I used the 42 bus to get to school in Tooley Street having to change at the Bricklayers Arms from New Cross. The last tram was ceremonially burnt in New Cross Gate outside the tram depot. The roads until then were surfaced with tarred wooden blocks which caught fire and needed to be put out as the tram burnt down to its chassis. This changed when they finally took out the tram lines and surfaced the roads with tarmac. In heavy downpours the blocks of tarred wood would be ejected as they swelled and it was always fun to watch who were the first ones to take the ejected blocks. We were guilty at times as we used them to start our coke stove, they were too smelly for the coal fire. Life was very different then.

LikeLike